According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cancer is the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020 (1). In addition, GLOBACAN estimated 19.3 million new cancer cases and almost 10 million cancer deaths in 2020 with breast, lung, colon, rectum, and prostate cancers being the most common cancer types (2). It is important to ensure that anticancer treatments are available to patients to improve their quality of life and reduce cancer-related hospital expenses and death. However, most cancer treatments are expensive and not available to all patients giving way to increasing interest in the concept of ‘generic’ oncology drugs. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 16 new cancer drugs and 5 generic cancer drugs in 2021 (3).

What are generic drugs and why are they so important?

Generic drugs are medications created to be the same as an already marketed brand-name drug in dosage form, safety, strength, route of administration, quality, performance characteristics, and intended use (4). Patent expiration and loss of marketing exclusivity of the brand-name or innovator drug molecules allow for manufacturers to produce generics. The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act or the Hatch-Waxman Act 1984 established several practices to facilitate the development and marketing of generic medications. The global generics market was worth $390 billion in 2020 and is projected to reach $574 billion by 2030 (5). In the U.S., 9 of 10 prescriptions filled are for generic drugs. Although generic medications contain the same active ingredient as brand-name medicines, they may differ in inactive ingredients or excipients and can differ in appearance. However, these differences should not affect the performance, safety, or effectiveness of the generic. The reason for the relatively lower cost of generics compared to brand-name medications is that they do not require extensive nonclinical (animal) and clinical studies. Since the manufacturers of generics save a lot of time and resources, generics are priced considerably lower than brand-name drugs. The lower cost of generics makes them affordable, and accessible to patients allowing for increased patient adherence, particularly in cases of chronic diseases.

How are generics approved?

The FDA approves generics via the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway also known as the 505(j) pathway. Generic applications are termed ‘abbreviated’ as they do not require extensive nonclinical and clinical studies to demonstrate safety and effectiveness. However, to be marketed generics must demonstrate that they are ‘therapeutically equivalent’ to brand-name medications. Therapeutic equivalence implies pharmaceutical equivalence (same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)) and bioequivalence. Two products are considered bioequivalent when they are equal in the rate and extent to which the API becomes available at the site(s) of action. Bioequivalence testing is the most critical requirement of ANDAs. Several oncologic drugs such as monoclonal antibodies and interferons are biologicals with complex structures. Biologicals do not have generic equivalents as their structures can differ slightly based on the manufacturing process and starting materials. The so-called generic counterparts of biologicals are known as biosimilars or follow-on biologicals and require extensive bioequivalence testing in addition to tests for safety and immunogenicity.

What are bioequivalence (BE) studies?

Bioequivalence (BE) studies compare the in vivo rate and extent of drug absorption of the brand-name medication (or reference listed drug (RLD)) and the proposed generic product. Typical studies are done in a 2*2 two-sequence, two-period, two-treatment crossover design in both the fasted and fed states in healthy volunteers. Comparison of pharmacokinetic endpoints such as area under the curve (AUC) and maximal drug concentration (Cmax) are mostly used. Two products are bioequivalent when the 90% confidence interval for the test/reference ratio of Cmax and AUC falls within 80-125%. The FDA has developed

product-specific recommendations for BE studies for several drugs including oncologic agents.

Considerations for Bioequivalence studies for Oncologic treatments

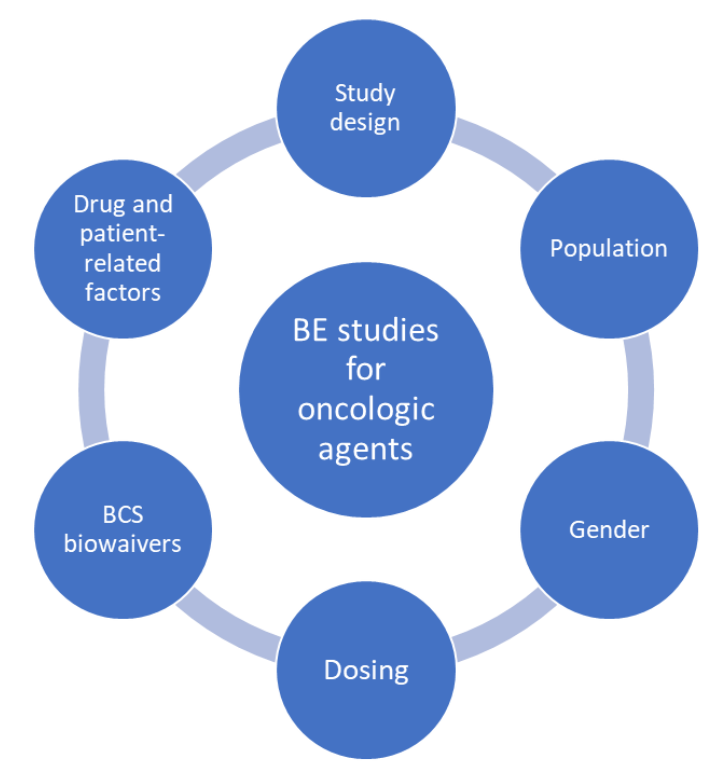

The following factors need to be considered when designing a BE study for oncologic safety keeping patient safety the utmost priority.

- Study design

Most BE studies are designed to be crossover studies in which the RLD and proposed generic product are administered to the same participant in a two-period, two-sequence pattern following randomization. Although the crossover design helps eliminate intra-subject variability as the subjects serve as their own control and reduces the number of subjects required for the study, crossover designs are not suitable for drugs that have long half-lives due to carryover effects that can affect the next treatment. In these cases, parallel designs should be considered in which subjects in the RLD and generic treatment groups are matched for various demographic characteristics.

- Population

Unlike BE studies for most drugs that include healthy participants, cancer patients need to be included in BE studies for oncologic agents. This is because of safety concerns and cytotoxicity of cancer drugs. Finding enough patients with similar cancer staging or diagnosis may be difficult for BE studies because of strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. Recruitment of patients using registries is recommended to meet target patient enrollment goals. In cases where the oncologic agent is non-cytotoxic healthy volunteers may be considered.

- Gender

In cases where BE studies are performed in healthy volunteers, it is necessary to ensure that the anticancer agent does not cause other undesirable side effects such as birth defects or teratogenicity. In certain cases, it may be recommended to include only male participants in the BE studies.

- Dosing

In BE studies done on cancer patients, it is important to ensure that the regular treatment schedule of the patient is unaffected. The anticancer agent should be administered at the same dose and schedule as done routinely so as not to affect the patient’s treatment response. Although the highest dose level of the drug is recommended for BE studies this may not be feasible for oncologic agents as the patient’s normal dose may not be the highest dose strength.

- Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) biowaivers

The BCS classifies drugs based on their solubility and permeability characteristics into four classes: I, II, III, and IV. Biowaivers for BE studies may be permitted for BCS Class I drugs that have a high solubility and high permeability as these drugs dissolve and are absorbed rapidly following oral administration. Due to safety concerns with oncologic agents, these compounds may not be exempt from BE studies even if they fall into the BCS Class I category as they are cytotoxic. In these cases, additional studies may be required, and an Investigation New Drug (IND) application may be necessary prior to conducting BE studies.

- Narrow therapeutic index

Most oncologic agents have a narrow therapeutic index meaning that they have the potential to cause dose-limiting adverse effects at or near doses required to achieve the desired therapeutic effect. In such cases, the bioequivalence criteria of 90% CI with 80-125% may be insufficient. The European Medicines Agency (EMA), Health Canada, and the FDA have proposed to tighten the limits to 90-111.1% according to within-subject variability in response and perform replicate studies.

Bioequivalence studies form the basis for approval of generic products as well as approval of products following manufacturing or post-approval changes. These studies are especially critical for oncologic agents that have safety concerns and therefore should be performed with utmost care to ensure the availability of affordable medications allowing for improved patient adherence.

References

- Cancer (who.int)

- Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries – PubMed (nih.gov)

- 2021 First Generic Drug Approvals | FDA

- Generic Drugs: Questions & Answers | FDA

- Generic drug market growth: insights to 2030 (europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com)